2. Collaboration: The Film Editor vs. the Director

If it is to be suggested that the editing role is one of legitimate artistry, then the lines between the director and the editor, specifically which one is the source of creativity or the ‘owner’ of the text, become blurred. Undoubtedly, there must be a back and forth between the two parties. Therefore, the director-editor relationship presents itself as one of the most vital cogs within the mechanics of professional filmmaking. This essentially alludes back to Gaut’s (1997, p. 150) theory of multiple authorship, at least in the form of a partnership between the director and the editor. In keeping with this, this discussion will provide an analysis of the various approaches and differing successes of some famous director-editor collaborations; how they relate to the perceived overlooking of the film editor, and indeed whether or not they suggest multiple authorship to be the most practical reworking of the auteur theory.

Director and writer David Mamet (1989, cited by Collard, 2010, p. 82) once quipped; ‘Film is a collaborative business: bend over’. While addressed with a sense of irony, this quote places the proposed hierarchy in film production in a convenient nutshell. It paints the director as a creative dictator, ultimately credited with responsibility for all aspects of the final film. This, as outlined by Ondaatje (2003, p. xi), is not the case, and is the mindset responsible for the overlooking, in particular, of the editing role. To a number of directors’ credit they do not play up to the myth, aside from in cases of marketing and promotion as discussed in chapter one. Indeed, directors Stephen Frears and Ken Loach, in interview, downplay their individual contribution and rigorously defend the notion of collaboration (Perkins & Stollery, 2004, pp. 49-51). In a similar defence, editor Tony Lawson offers a valuable insight into the editor’s contribution, defending the role’s creative merits in relation to that of the director;

Helping the director to achieve a ‘version’ of the film that he wants – to avoid the word ‘vision’. That’s not being a button-pusher, but interpreting his desires in a creative and practical way … The editor should work towards bringing the director’s wishes to the screen, and when the editor disagrees, to encourage, persuade, an alternative approach (Perkins & Stollery, 2004, p. 51).

Whilst this quote still implies a hierarchy placing the director above the editor, it also provides a real sense of the creative influence editors can exert in discussion with their collaborator. They are as much decision makers as they are followers of the director’s instructions, and act as a nurturing force for the film project as a result. For this reason, much thought and reason is needed, on both sides of the equation, before the collaboration is embarked upon. It is, as Rosenblum and Karen (1979, p. 69) allude to, a ‘marriage’.

This is not to say certain directors haven’t risen above the idea of collaboration and harboured almost exclusive praise for the success of a film. The creative split is not always 50/50 or even close to that. Directors such as Charlie Chaplin, Abel Gance, Harold Lloyd, and Buster Keaton would strive to keep creative control in the editing stage, often relegating their designated cutters to mere assistant editors (Rosenblum & Karen, 1979, p. 62). Other directors such as Renoir, Fellini, Hitchcock, and Bergman would essentially shoot films as they should be edited, leaving the editor with little room for creative manoeuvre (Rosenblum & Karen, 1979, p. 230). Regardless, even in these examples where collaboration has broken down somewhat, it signifies the creative importance of the editing process, if not the editor themselves, that the likes of Keaton ‘jealously guarded the editorial prerogative’ (Rosenblum & Karen, 1979, p. 62), knowing full well the potential for the cutter to dramatically influence the final film beyond a director’s vision.

This poses the question of whether such an act of leaving little to work with in the editing stage is ultimately counter-productive, putting the director’s vision over the good of the film as a whole. This idea is certainly not without precedent, as director’s visions are frequently altered drastically in editing to great acclaim. One important example of this is Edwin S. Porter’s silent film Life of an American Fireman (1903). The film is widely praised for introducing the technique of cross-cutting – that is, repeatedly cutting between two spatially separate scenes. In this example, the film switches between a burning building, and real-life newsreel shots of the firemen coming to rescue the woman inside. On this subject, Gessner (1962, p. 8) writes; ‘It would not be the first time that reality sharpened imagination, although this appears to be the first time in cinema. The climax becomes highly cinematic through parallel movements – simultaneous time – in a series of crosscuts, incredibly swift’.

Despite the praise, however, it is not completely clear the credit for the technique should lie with director Porter, as an earlier version of the film would surface years after its release without the use of this editing method. It was later re-cut by an unknown editor into the version familiar today (Musser, 1991, pp. 232-233). Returning to the idea of the ‘director’s vision’, Life of an American Fireman distances itself from this by achieving recognition as a result of an editing decision its director didn’t even make. Contrary to the theme of collaboration, however, Life of an American Fireman is still wholly credited to Porter – his ‘masterpiece’ (Gessner, 1962, p. 1) – despite the ultimate lack of vision on his part.

The case of Porter is an interesting one as, despite an apparent enforcing of auteurism upon him, his work precedes the popular rise of auteur theory in the 1950s. Yet he is a clear early example of perceived single authorship. The knock-on effect of this becoming commonplace was that the concept of the director as the ‘star’ would run rife, be it for reasons of marketing, or for legitimate cultural critique. The seeming necessity for the auteur title, and the subsequent earmarking of directors for this title, developed an ego amongst the forthcoming generation of directors that would lead to some tensions in collaboration.

The dictatorship enforced by such directors is summed up by Rosenblum and Karen (1979, p. 231);

By and large there is little harm done if a writer who works for a popular magazine imagines himself to be Tolstoy. But a director is fundamentally a leader, and such grandiosity stifles the contributions of subordinates, who are crucial to a film’s success. A director’s prideful resistance to any idea that is not his own – or not shrewdly planted in a way that allows him to believe it’s his own – is symbolic of the handicaps under which films have been made for the past twenty years.

They continue to write on this subject, referring to confrontations between the director and his ‘subordinates’ over creative differences; the arrogance exerted by the former, and the humiliation suffered by the latter as he is forced to bow down to the director’s wishes (Rosenblum & Karen, 1979, pp. 231-232). A key example they present is that of director Mel Brooks. Brooks initially suggested a ‘collaboration of equals’ between himself and editor Ralph Rosenblum for The Producers (1968). However, Brooks’ impatience and inexperience weighed down heavily and it led to heated arguments with those working on the film. Brooks would essentially ignore the advice of his more experienced subordinates, including Rosenblum, in favour of selfishly preserving his own creative vision (Rosenblum & Karen, 1979, pp. 196-201). On editing for directors like this, Rosenblum & Karen (1979, p. 233) later write;

Under the growing class of imperial directors, this work without acknowledgement, this crucial work that often figures significantly in the critical assessment of the director himself – a dependency that many directors keenly resent and therefore try all the more to deny – had begun to feel like slavery.

It was an observation that would lead Rosenblum onto collaborating, almost exclusively, with Woody Allen towards the end of his career. The relationship between the two would prove to be a stark contrast to that of Rosenblum and Brooks, operating mainly as equals, with Allen even submissive, when necessary (Rosenblum & Karen, 1979, p. 256). In discussion with Stig Björkman, Allen confirms the huge creative influence Rosenblum had, particularly in his first major directorial effort, Take The Money and Run (1969);

A scene would look very unfunny to me, and Ralph would say, ‘Look, what you have to do is put in the sound effects in the scene. You don’t think it’s funny because you’re not hearing anything’ … This happened to me any number of times. I would put a scene in in the laborious way that I wrote it, and he would say, ‘Why are you wasting your time with all that? Just use the first cut and the last cut and throw out the middle. You don’t have to show the character progressively go. You can just cut right in.’ Ralph showed me many, many things (Björkman, 2004, pp. 33-34).

The collaboration was an opportunity for Rosenblum, on behalf of all editors, to readdress the balance and even turn the tables on the director-editor relationship. He, and indeed Woody Allen, may have been sure of Rosenblum’s contribution to Allen’s films, but he was aware that those outside the industry weren’t. Reacting to this, whilst working as an editor on Bananas (Allen, 1971), Rosenblum would enforce a claim to the title ‘associate producer’, a self-confessed dummy title, or ‘interpersonal prop’, as he describes (Rosenblum & Karen, 1979, p. 256), in an effort for recognition.

Allen, unlike Brooks, was remarkably accepting of his material being trimmed, altered, or dropped entirely, in the editing stage. It was this kind of artistic compromise that allowed him and Rosenblum to form such a solid collaboration across five of his next six pictures (Rosenblum & Karen, 1979, p. 256), a collaboration that was perhaps the first famous example of the metaphoric ‘marriage’ discussed earlier. In the decades that followed, reoccurring director-editor partnerships would become a popular theme in filmmaking. The relationship regularly seems to hinge on a backing down of one side, however, reinforcing the idea of a hierarchy in film production. Without some form of compromise, tension builds and the film suffers, as with Rosenblum and Brooks.

The rise of female editors in the 1920s suggests many directors and studios may have foreseen this. Indeed, Margaret Booth was employed by MGM for several decades as both an editor and supervising editor, overseeing up to forty-two of their pictures a year and cutting some of their most famous, such as The Mutiny on the Bounty (Lloyd, 1935) (Seger, 2003, p. 16). According to Rosenblum and Karen (1979, p. 69), directors found in female editors the ‘ideal combination of aptitude and submission’. This allowed for a successful partnership, whilst continuing to protect the director’s overall vision. Booth herself seemed to submit to this theory, as quoted by Seger (2003, p. 17);

In life, as in editing, we [women] may wield little power, but we exert great influence. We may not participate as players but we observe … Historically, men do and women watch. As a result, women have an intuitive sense of what is true in human behaviour … Editing is about making choices based upon observation.

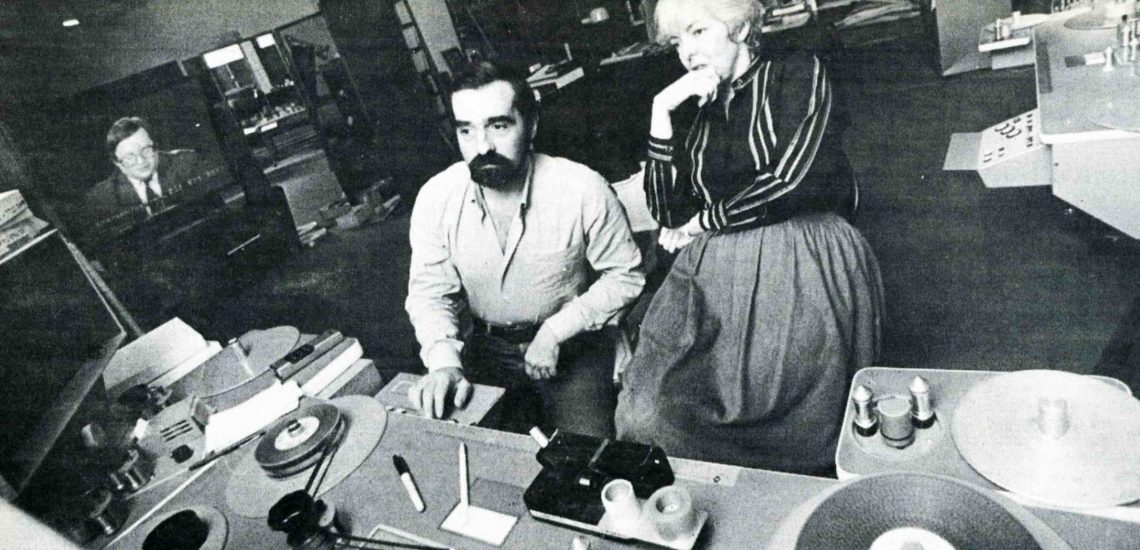

It may be an old-fashioned view of women, but it stayed the course, as many of the most noteworthy names in film editing history happen to be female. Verna Fields, famous for working alongside George Lucas and Steven Spielberg on American Graffiti (1973) and Jaws (1975), respectively, and Thelma Schoonmaker, a long-term collaborator of director Martin Scorcese, are amongst this list. Even Woody Allen would end up working exclusively with a female editor, post-Rosenblum, collaborating with Susan E. Morse on all his films from Annie Hall (1977) onwards (Seger, 2003, p. 16). The foremost modern example, however, is Sally Menke, editor of all of Quentin Tarantino’s directorial efforts until her death in 2010. In the documentary The Cutting Edge (Apple, 2004), Tarantino refers to the process of editing as the ‘final draft of the script’, underlining its creative importance. With regards to Menke’s role in this, he says; ‘I write by myself but when it comes to editing, I write with Sally. It’s the true epitome, I guess, of a collaboration because I don’t remember what was her idea, what was my idea. We’re just right there together’ (Walters, 2010).

Tarantino, widely celebrated as an auteur (Aftab, 2009), again alludes to the idea of multiple authorship, propelling Menke to almost equal status with him. However, the so-called submissive nature of the female editor in such a partnership still proves to be an important factor. Tarantino may imply a sense of equality between him and Menke, but he also underlines the necessity of him working with a female editor as opposed to a male editor. In The Cutting Edge, he states that he expects a female editor to be much more ‘nurturing’ to the film. He later explains that a male editor would try ‘to win their way just to win their way’, or ‘shove their agenda’ at him (Walters, 2010). It could be argued from this that Tarantino, just like Buster Keaton, protects ‘his’ film when it comes to the editing stage. There are gender and sexism issues of course, but the implication is that directors such as Tarantino and Scorcese utilise the female editor to nurture their own creativity, as opposed to forming a true artistic collaboration with a male editor along the lines of Allen and Rosenblum.

Noticeably, others directors have found a variety of other ways to protect their artistry in the editing stage. Indeed, it is not uncommon for certain directors to forgo the need for an editor entirely, and take on the role themselves – prioritising the process over the individual. Amongst the most famous examples of this, are Joel and Ethan Coen. If the auteur title is to be insisted upon, then the Coen Brothers, as a unified whole, are perhaps the perfect candidates to acquire it; having written, produced, directed, and edited the majority of the films bearing their name. Though considering them as Joel and Ethan, individually, again reinforces the idea of collaboration over auteurism. Speculation remains rife as to which brother takes which roles in the Coens’ films. On this point, Robson (2003, p. 20) quotes Ethan; ‘Joel talks to the actors more than I do and I probably do production stuff a little more than he does’. Despite the fact he states the roles are ‘largely overlapping’ (Robson, 2003, p. 20), brother Joel claims; ‘Psychologically, it’s sort of important to us to realise that Ethan produces the movie and I direct … so, in a sense, we don’t want another producer or director … That’s sort of why we keep it separate that way, but it doesn’t really reflect what happens on set’ (Robson, 2003, p. 20).

This is another, more extreme, example of creative talent guarding their artistry on a film production, yet it sidesteps the issue of compromise. For the Coens, this carries on into the editing stage. What is interesting is how they attempt to distance themselves from the process, despite the fact they are the designated editors. Since Blood Simple (1984), the Coens have been associated with editor Roderick Jaynes. Jaynes is, however, fictitious and merely a pseudonym for the editing work of the brothers themselves. Robson (2003, p. 20) speculates that, along with the separation of the producer and director titles, this was a method of dissipating their perceived ‘brotherly dominance’ over the production of Blood Simple, worried that combining all of the roles may have isolated an audience that by this point, had a greater understanding of the mass collaboration involved in feature filmmaking.

Whilst Roderick Jaynes may act as a figure of fun for the Coens, to the point where they have even provided him an elaborate back story and fictitious filmography (Robson, 2003, pp. 21-22), it can be argued that the idea the brothers would create this alternate personality suggests at least an acknowledgement of Lawson’s (2004, cited by Perkins & Stollery, p. 51) stance that a director needs the editor to provide a fresh, alternative angle. In the case of the Coens, they use the character of Roderick Jaynes to separate themselves from their own work, in much the same way a non-fictitious editor would be used to provide unbiased fresh eyes to somebody else’s directorial work.

In a sense, it is these fresh eyes that make the notion of an effective director-editor collaboration seem so important. The Coen Brothers may not have a distinguished editor to provide such fresh eyes, but they are at least collaborating with each other throughout the process. Woody Allen’s films similarly benefitted from the experienced input of Ralph Rosenblum, whilst Mel Brook’s refusal to collaborate in the same manner with Rosenblum may have negatively affected the creation of The Producers. Of course, the idea of collaboration extends beyond just the editor and the director, a big budget feature film naturally requires many creative and technically gifted individuals to combine their talents. However, as discussed throughout this chapter, the editing stage is a contentious issue, often even a power struggle. This naturally presents the specific partnership between the director and the editor as where a film can be made or broken, as the idea of ‘finishing’ the film creeps into both of their thought processes. Consequently, as the idea of collaboration acts as the biggest argument against the implementation of the auteur title, it is difficult to argue that either the director or the editor can individually lay claim to it. Instead, what seems apparent is that, in certain cases at least, a film’s editor merits an elevation in prestige to match the director. The two roles working in tandem adds much credence to the idea of a shared authorship.

Leave A Reply